Understanding the intricate physics behind particle transport through cleanroom door gaps is essential for maintaining stringent ISO classification standards and protecting sensitive processes.

Even microscopic openings can serve as conduits for contaminants, driven by complex fluid dynamics and pressure imbalances that challenge traditional containment strategies.

This article explores the mechanical forces at play, from air velocity gradients to the transient effects of door movement, providing a technical foundation for contamination control.

By mastering these physical principles, facilities can optimize their HVAC performance and safeguard the integrity of high-stakes pharmaceutical and semiconductor environments.

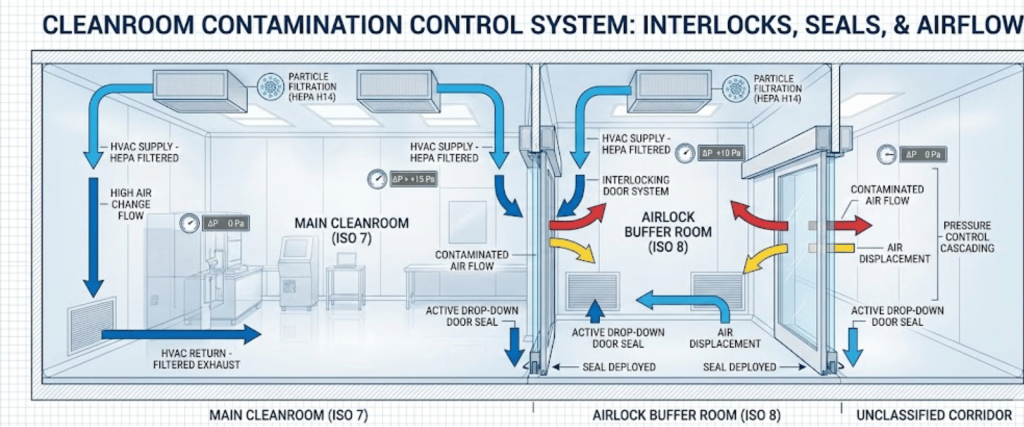

In the world of cleanroom design, the most fundamental defense against contamination is the positive pressure gradient. According to Bernoulli’s Principle, air moves from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure.

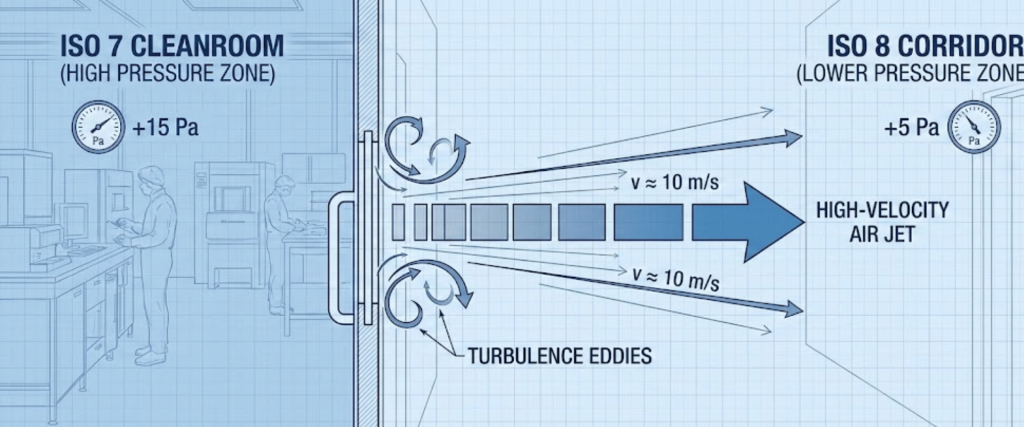

In a standard ISO 7 cleanroom, a higher pressure is maintained relative to the surrounding ISO 8 corridor. However, when a door gap exists, this pressure difference creates a high-velocity air jet.

While this outward flow is intended to push particles away, turbulence at the edges of the gap can sometimes create eddies that allow particles to sneak against the flow or remain suspended near the seal.

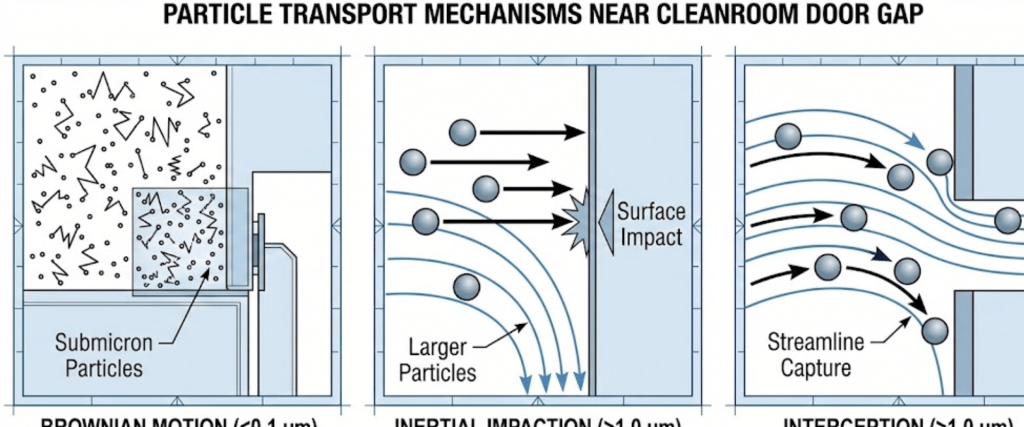

Particles do not simply move in straight lines; their transport is dictated by several physical phenomena depending on their mass and size.

Extremely small particles ($<0.1 \mu m$) move erratically due to collisions with gas molecules. These particles can drift through gaps even against low-velocity air currents.

Larger particles ($>1.0 \mu m$) have more mass. If the air changes direction quickly near a door gap, these particles may continue in their original path due to inertia, potentially striking surfaces or entering the gap.

This occurs when a particle follows a streamline of air that passes within one particle radius of a surface (like the door frame), causing it to stick.

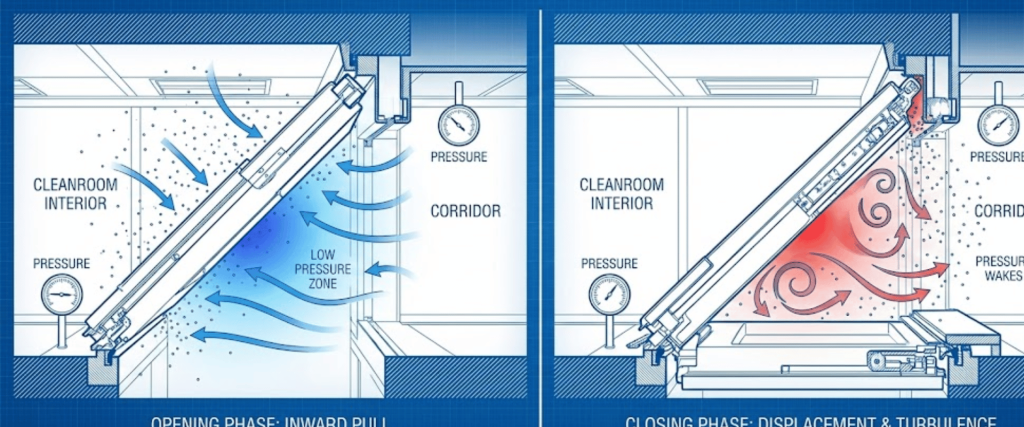

The physics of a static door gap is vastly different from a door in motion. When a swinging door opens, it acts as a piston.

Research suggests that the volume of air exchanged during a single door opening can be significantly higher than the leakage through a static gap over several hours.

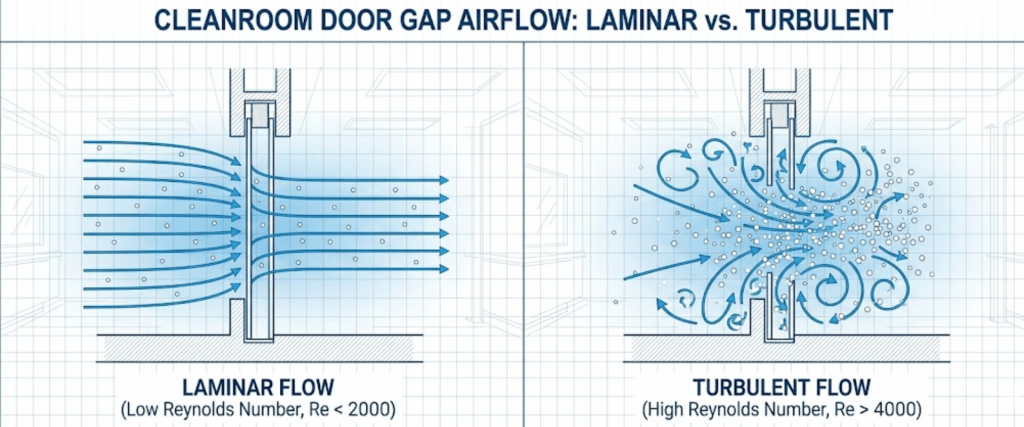

The rate of particle transport is heavily influenced by the geometry of the gap. A thin, long gap (the space between the door and the floor) creates more friction and resistance to airflow than a wider, shorter gap.

The velocity of air through these gaps is calculated using the formula.

$$V = K \cdot \sqrt{\Delta P}$$

(Where $V$ is velocity, $K$ is a constant related to air density and gap geometry, and $\Delta P$ is the pressure difference).

If the velocity drops too low due to an undersized HVAC system or poorly sealed doors, the protective air curtain effect is lost, making the room vulnerable to back-diffusion, where particles move against the intended direction of airflow.

Airflow through a door gap isn’t always smooth (laminar). In many cases, it is turbulent. Engineers use the Reynolds Number (Re) to predict this.

To counteract the physics of particle transport, modern cleanrooms employ several engineering controls.

The transport of particles through cleanroom door gaps is a complex interplay of fluid mechanics, particle physics, and mechanical design.

By understanding that contamination is not just about holes but about the behavior of air and mass under pressure, facilities can design better containment systems.

Pressure differentials create a continuous outward flow of air through any available opening. This air curtain ensures that even if a physical gap exists, the higher internal pressure acts as a mechanical barrier, pushing microscopic contaminants away and preventing external air from drifting into the controlled environment.

Rapidly opening or closing a door creates a piston effect, which generates a temporary low-pressure wake. This turbulence can physically suck unfiltered air and particles through the gap, momentarily overcoming the room’s positive pressure. Controlled, slower movement helps maintain stable fluid dynamics.

A cleanroom can remain compliant only if the HVAC system is powerful enough to maintain the required pressure gradient ($\Delta P$) despite the leaks. However, visible gaps significantly increase energy costs and the risk of back-diffusion, making the use of high-quality gaskets and drop-down seals a best practice for long-term ISO compliance.

Since 1992, Applied Physics Corporation has been a leading global provider of precision contamination control and metrology standards. We specialize in airflow visualization, particle size standards, and cleanroom decontamination solutions for critical environments.